Bending ice generates electricity, potentially sheds light on the long-standing mystery of lightning

An international research team consisting of researchers from the Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (ICN2) in Spain, Xi'an Jiaotong University in China, and Stony Brook University in the United States has discovered for the first time that ordinary ice exhibits the ' flexoelectric effect ,' meaning that ice generates electricity when bent.

Flexoelectricity and surface ferroelectricity of water ice | Nature Physics

Scientists find that ice generates electricity when bent

https://phys.org/news/2025-09-scientists-ice-generates-electricity-bent.html

The ' piezoelectric effect ' is a well-known phenomenon in which electricity is generated by applying force to a material. This is a phenomenon in which an electric charge is generated when pressure is applied to certain materials such as quartz, and is used in everyday applications such as the flint in a lighter.

by

The flexoelectric effect is a phenomenon in which electric polarization is induced by deforming a material. Water molecules ( H2O ) have an electric bias (polarity), but the ice crystals we see every day have a structure in which the polarity cancels out as a whole, so they do not exhibit the piezoelectric effect that generates electricity even when pressure is applied. On the other hand, the flexoelectric effect does not depend on the symmetry of the material, so it can occur universally in any material. Focusing on this point, the research team conducted the following experiment to measure the previously unknown flexoelectric effect of ice.

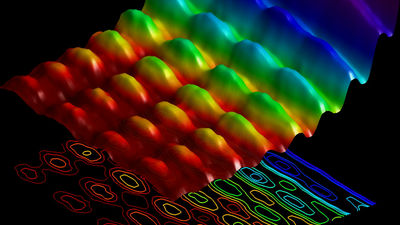

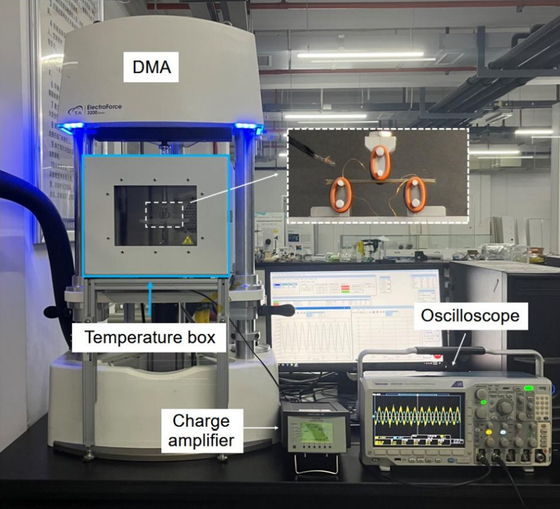

The research team first created 'ice capacitors' (1.8 to 2.2 mm thick) by sandwiching ultrapure water between two sheets of gold- or platinum-coated aluminum foil and freezing them at approximately -20°C (253 K). They then placed these ice capacitors in a dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA) and subjected them to periodic deformation by three-point bending.

The deflection (amount of deformation) of the central part was measured with a displacement sensor, and the minute electric charge generated by the bending was amplified and measured with a charge amplifier, and both were synchronously recorded on an oscilloscope. From this data, the relationship between the degree of bending of the ice and the resulting electrical polarization was analyzed.

The researchers calculated the flexoelectric coefficient, an index that indicates the ease with which electricity is generated by bending, and found that the flexoelectric coefficient of ice was comparable to that of ceramics, which are also used in sensors. Furthermore, at temperatures above 248 K (-25°C), a 'quasi-liquid layer (QLL)' began to appear, which has liquid-like properties at temperatures below the melting point where the surface of the ice completely melts. The flexoelectric effect rapidly intensified, and the ice became more susceptible to deformation.

Furthermore, when the temperature was lowered below 203 K (-70 °C), the flexoelectric effect began to increase again, peaking at about 160 K (-113 °C). 'We found that ice has a strong ferroelectric layer on its surface at temperatures below -113 °C,' explained Wen Jing, co-author of the study and a researcher at ICN2.

Ferroelectricity is the property of spontaneously polarizing ice without the application of an external electric field, and of being able to reverse that polarization with an external electric field. While ice normally does not exhibit ferroelectricity, the research team concluded that this phenomenon is 'surface ferroelectricity,' occurring only in a very thin layer of ice, just a few tens of nanometers thick.

The team then tested different electrode metals, but the results still strongly suggested that ferroelectricity was induced on the ice surface. The team argues that ice can generate electricity in two different ways: ferroelectricity at temperatures below -70°C, and flexoelectricity at temperatures above -25°C.

One of the insights gained from this research is the mechanism by which lightning occurs. It is thought that repeated collisions between small ice particles in thunderclouds cause electric charges to separate, creating a huge potential difference that leads to lightning discharges. However, it has long been a mystery why ice, which has no piezoelectricity, becomes charged by collisions.

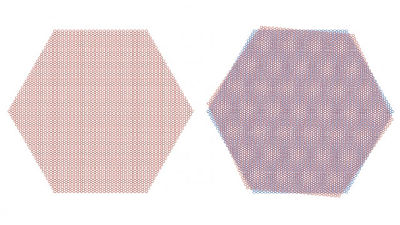

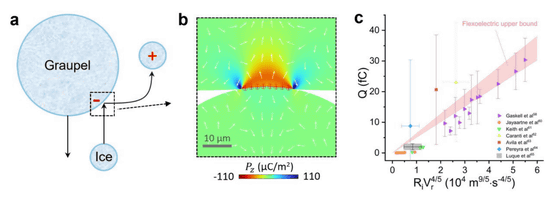

The research team modeled the collision of ice particles in clouds and calculated the amount of charge generated by the flexoelectric effect. They found that the ice particles deform significantly during collisions, generating a large potential difference.

The left side of the figure below shows a schematic diagram of a collision between hailstones and ice particles. The collision causes a separation of electric charge, with the hailstones becoming negatively charged and the ice particles becoming positively charged. The center shows the simulated potential difference caused by the flexoelectric effect at the moment of collision, and the graph on the right compares the predicted values (pink) with previous experimental data (dots). The research team reported that the predicted values 'matched very well' with the amount of charge transfer per collision reported in previous experiments, and stated, 'Our results suggest that the flexoelectric effect may be able to explain the mechanism by which lightning is triggered.'

The research team also hopes that this discovery may be applied to the production of power generation elements using ice in cold regions.

Related Posts:

in Free Member, Science, Posted by log1i_yk